Despite this being our third time at Glacier, I transcend as we ascend the mountains on Going to the Sun Road. Then Fleetwood Mac’s “Landslide” plays on rotation and I’m unearthed. Something about that song’s major/minor key shifts still tug at me after all these years, and that’s without America’s most breathtaking drive as visual backdrop.

We first crossed this pass in 2000 with Zach and Annie bickering in the backseat. In 2004 they couldn’t join us due to work and school commitments, so 13-year-old Taylor had nobody to fight with as we approached the summit, though that didn’t stop him from voicing his displeasure of having to take this Glacier trip with his parents. (Tay grew to love the park during college church trips.)

Jim and I wanted to visit Glacier again before we got too old to drive to it or too old to hike it. This time, we replace the complaints of our kids in the back seat with the crooning of Stevie Nicks in the front speakers.

Glacier Park has tightened its rules in recent years. Administrators had to do something as Going to the Sun regularly turned into a bear jam even with no bears around. Three years ago, they instituted a strict reservation system not only for lodge rooms, but for park entry. Today Glacier welcomes a similar numbers of visitors as before, just staggered throughout the days and months of its 15-week season.

To secure a lodge room at Glacier, you have to log into their website 13 months ahead of time on a specific day of the month at precisely 12 PM mountain time.

I practiced the reservation system a month early then coached Jim on the process. Since we planned to stay at two different lodges, we’d each tackle one booking. At least that was the idea. Moments before the stroke of Montana midnight, Jim’s log-in froze, so the whole operation fell to me.

In a panic, I selected the wrong room at Many Glacier Lodge and had to start over. In that two-minute delay, all the view rooms disappeared. We ended up with “mountain view,” a.k.a. parking lot.

I’d not have minded so much except I remembered our mountain view unit from 2004, a room which loomed over the employee smoking table; the cigarette fumes somehow flowed directly into our window. We didn’t spend a whole lot of time in that room.

But there we dozed at 2:30 AM when the fire alarm went off. I scrambled for my shoes and room key while Jim gathered his cameras: priorities. (Safety tip—During a hotel fire, grab your key since a smokey exit may require taking refuge back in your room. But don’t necessarily grab your electronics.)

The clanging roused Taylor from his teenage stupor. He hollered at us, “We gotta leave! RIGHT NOW!!” And we did, with key in hand but no cameras.

Other pajama-ed guests filtered down the hall and into the lobby of this old wooden tinder box of a lodge. Decades earlier, with Many Glacier in decrepit state, officials considered torching the place. “All we’d need is a gallon of gas and three matches,” one suggested.

But Many Glacier was spared from flames then, and again for us in 2004.

Standing in my bathrobe and Nikes, I overheard the hotel manager on the phone with fire officials explaining how someone had accidentally bumped an alarm, setting it off. All good.

Fast forward to 2024, we begin our Glacier visit at Lake McDonald Lodge. I couldn’t book our McDonald room until I’d fixed my Many Glacier error, and my setback resulted in another parking lot view room. But I was grateful as ten minutes later there were no rooms available at all.

Turns out, our Lake McDonald room offers a view more of rooftops than parking lots, and it sits on a corner with no employee smoking section below, so we consider it a win. Busloads of visitors stream into the lobby throughout the day, but we discover a comfy and overlooked seating area overlooking the action.

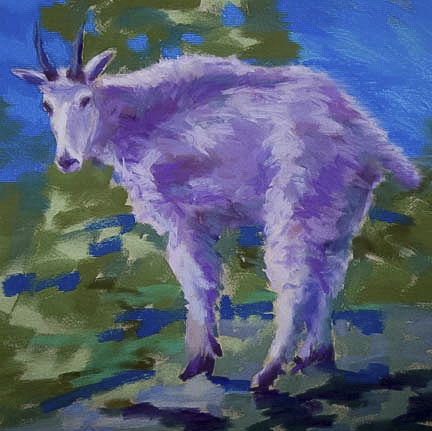

A stuffed mountain goat monitors us on our mezzanine perch, bringing to mind the Glacier goat Jim painted from 2004, a pastel piece with a lavender hue that made its way into Annie’s various bathrooms as a college student and young adult. For years, her guests would comment on her purple goat after washing their hands.

A bunch of other taxidermied creatures join the goat in McDonald’s lobby in a representation of Glacier’s animal kingdom. Native American pictographs blanket the orange light fixtures throughout the lodge. These decor choices might raise eyebrows back in Oregon, but we’re in Montana now.

Next we move onto Many Glacier Lodge. We receive our key and hunt for our parking lot view quarters, yet our room number suggests the opposite side of the hotel—the view side. Have they made a mistake? But the key fits, the bolt turns, and we gaze directly onto Swiftcurrent Lake.

We consider Glacier’s 13-month reservation requirement. A lot can happen in 13 months. A woman can have a baby—start to finish—plus maybe train her infant to sleep more than two hours in that time span. Or maybe train her husband to get up with the baby in that time frame.

Perhaps other guests had to drop their bookings because of—well, life—and we rose the ranks?

We never learn how we scored our room upgrade, but we don’t dare look a gift goat in the mouth. We simply survey God’s creation of lakes and mountains from our window and deck. I stare at it now as I type.

Besides the view, we partake in Many Glacier’s entertainment, including the free “hootenanny” talent show which staff performs each week in the lobby. Adorned in his lederhosen uniform, a bellman with long, stringy blond hair serves as emcee. He kicks off the evening’s program with a recitation of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18: Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day…

A couple hours later I watch him empty the garbage cans in the baggage drop-off area out front.

Other staff present a wide-range of talent, the audience rapt at all extremes of ability. Besides church congregations, I can think of a no more appreciative or forgiving audience. I wonder if applications for work at Glacier Park lodge include sections for hootenanny skills, such as the dad-joke-telling and cowboy-poetry-reading we witness.

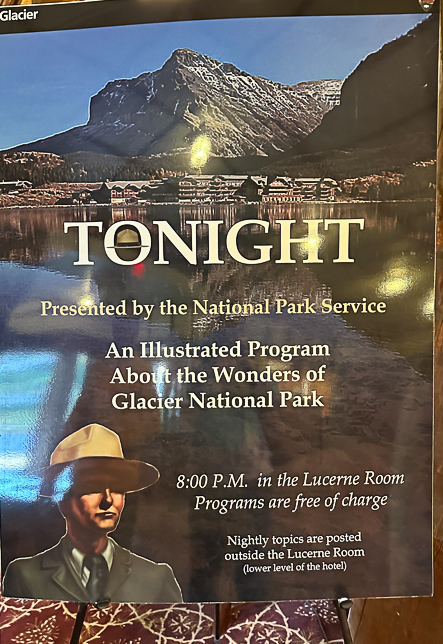

After the hootenanny, we attend a park ranger talk in the lodge basement. Nobody cares about the topic because it is, you know, a park ranger talk. To us, this qualifies as the national park equivalent of Disneyland’s hottest ride. Even better, talking rangers with wide-brimmed hats come free and don’t require standing in line for two hours.

Tonight’s lecture subject? Bats.

Our visiting ranger from neighboring Waterton Lakes National Park speaks about bats in that charming Canadian way reminding us of boots. Within a half hour, she has us all convinced that we love these flying blood-sucking mammals more than we ever realized—particularly upon learning that they can consume upwards of 1,000 blood-sucking mosquitos per day.

The next afternoon, we take a hotel tour led by the charismatic Laura, a retired ranger and current volunteer. Laura began her Many Glacier career in 1980, back when they referred to housekeepers as maids and made them dress like Heidi.

Laura explains how Mr. Tippet, the hotel’s eccentric manager during the Reagan era, decided they needed hootenannies and musicals to draw guests’ attention from the building’s decayed condition. He recruited a diverse group of theater and music majors (like Laura) and assigned staff as follows:

1. Theater and dance students waited tables.

2. Music majors cleaned rooms.

3. Southerners covered the front desk.

4. Ivy Leaguers washed dishes.

Staff covered nine hour shifts then rehearsed for the evening show, including at one point, full Broadway musicals. Word spread and music students from around the country flocked to work at Many Glacier Lodge.

Tippet also hired geologists and history majors to drive the park’s red jammer buses and athletes to operate Glacier Park Lodge. To boost moral, he had employees from his different factions compete in flag football and soccer. The athletes crushed the music majors pretty awful but nobody seemed too surprised or upset.

After completing her music education, Ranger Laura returned to school for a couple of business degrees then scaled the heights of national park service. She served for thirty years at Glacier and Grand Canyon and finally park headquarters in Washington, D.C. before retiring.

Laura explains that her youngest daughter just left for college and she needed something to distract herself. She phoned Glacier—her favorite park—and asked if she could volunteer for the final weeks of the season. They said yes.

Laura begins her hotel and ranger talks by playing a tune on the same piano she used back in 1980 as a music-majoring maid. She wrote the song for the wedding of a couple of rangers who met and married at Glacier long ago.

I could write a lot more now, but I need to go on a hike with my own sweetheart, so that’s what I’m going to do. We did a bunch of other good stuff on this trip but I probably won’t cover it unless we encounter a grizzly bear or a lavender goat because how could I not, except to say that Jim’s already floating that we need to find a way to get back to Glacier again someday.